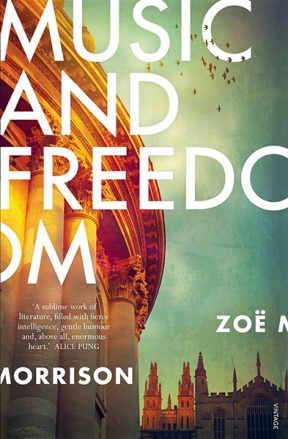

Zoe Morrison: Music and Freedom

by Jennifer Bryce

This first novel of Zoe Morrison has helped me to pursue my interest in the challenges faced by women artists in the first half of the 20th century – the challenges of being assumed to be second-rate compared to men, of believing that home-making should have priority over piano practice, of being dependent on men for money. Recently I’ve been interested in the lives of Australian pianists from that time: Margaret Sutherland and Eileen Joyce. Although these women weathered considerable difficulties, they had a better time than the fictitious Alice Murray in Zoe Morrison’s book.

Alice grew up on an orange orchard somewhere near Mildura. A difficult childhood was on the cards, with isolation, poverty and her parents’ deteriorating marriage. But Alice’s mother recognised that her young daughter was a gifted pianist and (finding the money somehow) sent her off to boarding school in England.

Alice would have been about eleven when she travelled to England by herself. She never sees her parents again. I was a little surprised that she didn’t pine for them more, but as a young prodigy she is intent on learning all she can about playing the piano. After completing school, she wins a scholarship to the Royal College of Music and at a workshop in Oxford, meets the young(ish) man who will become her husband. It is clear that Alice has no choice. Her parents have just died, leaving her nothing, and she must marry this comfortably-off professor in order to survive, even when her infatuated late-teenage heart allows her to have some misgivings.

The brutality of the marriage (we would now call it domestic violence) is almost unbelievable. And Alice is totally trapped. Music gives her some identity, some raison d’être. But she loses that. When she ultimately does have the opportunity to give a public performance of the Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 2, she develops a kind of arthritis that surely has a psychological genesis and, her husband forcing her to play, she makes a huge mess of it – she has lost everything; parents, country of birth, and now any remnant of hope.

At the beginning of the book we see Alice in late middle age. Her husband has died, but too late for her to make anything of the career she might have had. She has a son, a successful composer, who has inherited some of her musical ability. But Alice is starving herself to death and burning her husband’s research papers – severely unhinged – going for walks late at night and lying in a bog, following a simple routine of burn, file, call (presumably her son – she would hang up when he answered), play. She would play just one note on the piano, usually A, the note on which a symphony orchestra tunes, ‘Everything playing that note until it all faded and the silence began, that anticipatory silence between tuning and performance, although now there was no music because I had not played for many years’ [page 2]. One day she hears playing through the wall of her terrace house. At first it is just her A repeated. Ultimately she is able to help the young woman pianist who is practising the Rachmaninoff No. 2. In a sense this recues her. While the wall has a metaphoric role, providing a barrier between the life that might have been Alice’s and the grim reality of her existence, this involvement gives her strength to have some belief in herself. At one point she takes to her grand piano with an axe – a suggestion that music will not control her life now. Although the context is very different, this act reminded me of Eileen Joyce’s decisive closing of the piano lid at the end of her career.

Emily, the young woman on the other side of the wall, falls in love with Alice’s son and they have a child – thus Alice has a family for the first time. Over the next few years Alice becomes a writer and returns briefly to the home of her childhood. At the end of the book is a radio news report announcing that Alice Murray died at the age of 85, a writer of sufficient success for her death to be mentioned on BBC Radio 4.

Zoe Morrison is a pianist and has also worked professionally with victims of domestic violence. This combination of experience has led to a book where the sense of performing music is immediate: ‘Emily was playing parts of the concerto as if she were surfing it, as if the music were a wave coming towards her and she was pushing herself towards it . . . becoming part of it’ [page 251]. Earlier, there is a description of playing the Rachmaninoff Prelude Op.23 in D major: ‘I noticed its tendency to return to the tonic, the D. It was as if the piece were an ode to the note’ [page 71]. Descriptions of Alice’s terrible marriage – her inability to escape from it are poignantly real, from the pen of one who has insight into such situations.

The book is written in short chapters, each headed by a date, making an easy transition from Oxford to Australia; Alice writing the book and reflecting on her life in Oxford. Throughout most of the book we grapple with descriptions of a horrific marriage and the thought of what might have been if Alice had been able to pursue her career. One can’t ignore the unspeakable violence, but, given Eileen Joyce’s career, I wonder whether Alice would have had a satisfying life as a concert pianist? Maybe she ended up achieving greater satisfaction through her writing.

Reblogged this on Elwood Writers and commented:

The latest from Jennifer’s blog.

LikeLike

Thanks Barry!

LikeLike

Pleasure, Jenny!

LikeLike

Thanks, Jenny. A most comprehensive review of the novel.

LikeLike

Thanks Margaret — hope it didn’t spoil it for anyone by giving away too much.

LikeLike

Just finished Music and Freedom, at 6 am this morning. I don’t think I’ve ever read another novel where the music is so central and so beautifully described – page after page after page – and where the experience of experiencing music, in detail, note by note, passage by passage, is so beautifully conveyed. We understand just how much it can mean to someone – to us – it can turn into the whole of life. All three main characters – and they dominate 95 % of the novel – are musicians, while the other main character – the narrator’s violent husband – is a Friedmanite economist. The metaphor is obvious: music is life – and love; economics is inhuman – and death and violence; but nevertheless wonderfully carried through a book which flows, like life, and is hard to put down once started. I hope it wins many awards. It’s easily the equal of the half dozen or so Booker contenders I read last year.

LikeLike

Thanks Tony — yes, it’s an easy book to read, yet, as you suggest, it shows us how music can be life and love. I like your suggestion about the metaphors posed by music and economics.

LikeLike